The Liberated Method - Rethinking Public Service

© 2023 by Mark A Smith is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

Mark Smith

Senior Responsible Officer, Changing Futures Northumbria & Director of Public Service Reform, Gateshead Council

25th August 2023

Introduction: From buttoning down to freeing up…

We need to stop trying to improve services. If you start with services as your focus for change, you end up with services. People don’t want services, certainly not those that have a lot going on in their lives. People want support, relationships, practical help. People want to be understood.

So instead of starting with services, here in Gateshead and more recently across Northumbria, we started with people.

When you start with people and work outwards from them, things don’t look like services anymore. They look like things we would recognise when we go home (if we’re fortunate). They look like family, agency, community, relationships and understanding. They look like things humans are good at.

Designing public services around relationships is far more effective. People who have bounced around various public services for years start to positively change how they see themselves, the community, and the world when they’re contributing to a relationship and are understood.

Public services are under constant pressure to transform and redesign services to ‘find efficiencies’. When we focus instead on efficacy, we get better results for less money. No efficiency focused service redesign can do that.

When we compare what building relationships and community achieves compared to a service delivery mindset, it teaches us that it’s impossible to be efficient if we’re not effective. Efficiency, that mainstay of public service reform, is overrated.

Austerity though has driven a plausible desire to make things more efficient. by buttoning down processes, protocols, pathways, eligibility criteria etc… But this has made it worse. People are understood less and thus present more and more unresolved issues as part of a slew of rising demand. It’s demand we can design out, provided we focus on being effective. To do that, we need to move from a focus on efficiency to efficacy, and to do that needs a move from buttoning down to freeing up.

This article sets out how a liberation mindset can create positive reform. The ‘Liberated Method’ has been developed over a series of prototypes over the last five years and initially focused upon freeing up the creativity and compassion of front-line caseworkers (the name ‘Liberated Method’ comes from them). It has since grown to include liberating leadership, partnership, commissioning, and governance. To sustainably learn how to be effective in public service, particularly in supporting those that need it the most, we need to liberate all these things together.

But effective in doing what? No amount of liberation of things that exist within and between organisations counts as much as liberating peoples’ own internal capacity for change. Public services do not singularly transform lives and communities. What they can do is to support people by helping them to create the conditions to effect the changes they feel compelled to make.

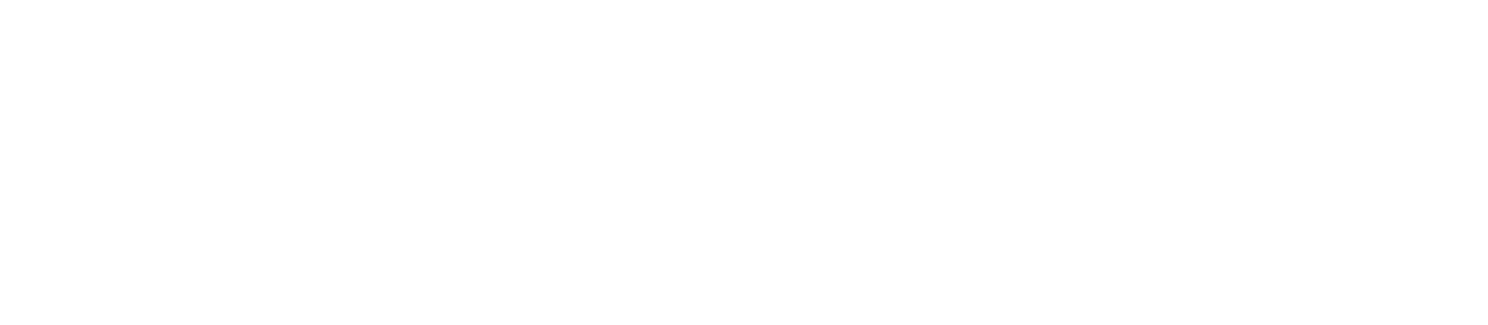

By acknowledging this, public services stand a far better chance of being effective and of liberating people’s own power for internal change. It’s this phenomenon, the combination of extrinsic and intrinsic support and resource, that lies at the heart of the Liberated Method.

Reforming reform – from navigation to relationships

Perspectives will vary, but it’s not a wild take to suggest that the purpose of public services is to help people to thrive.

Public services are generally designed around specific, describable problems (e.g., debt, diabetes) or specific and observable consequences of them (e.g., addiction, homelessness)

The wider system of services that has evolved over the last 80 years is predicated on the idea that services can solve problems. This would mean people with lots of problems need lots of different services. Providing lots of services to address an increasing range of problems and consequences does not appear to have worked, with demand rising and deepening across many public services.

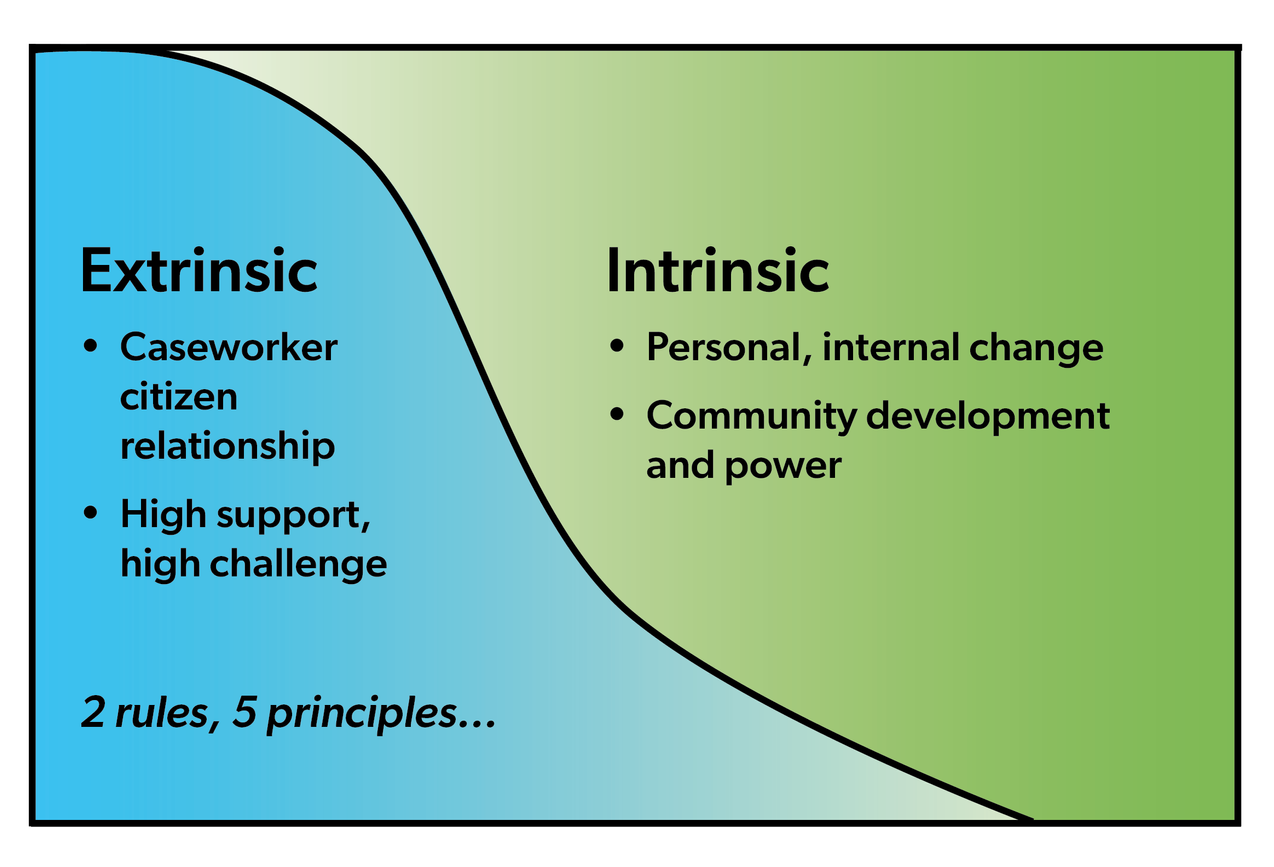

Those with a lot of connected and acute problems are deemed to be ‘complex’ or have ‘multiple and complex needs’. For such people, efforts to reform services that might help them and to address rising demand is often framed as a ‘navigation’ problem, i.e., how can we help people access the services they need? This despite there being little evidence as to whether services are having the desired effect; measures of efficacy are rare compared to those of industry or compliance.

Rising demand and reducing resources has also led to pressure to somehow do more with less, thus also creating a focus on efficiency as a goal.

With navigation and efficiency as goals for increasingly hard-pressed public services faced with rising inequality, issues such as method and efficacy were seldom as fruitful and accessible arenas for reform and yet these are the fundamental questions, i.e., what do we do, and how well does it work?

Focussing upon efficiency and navigation has created a public service reform ethos and industry that focusses inwardly on navigating and changing structures and operations. This has not created notable reform and has taken the focus away from the reality of people’s lives, their problems and their context, in particular their own capacity to shape and change their own lives.

For over a hundred years, people in the recovery community have transformed themselves from destitution and destructive behaviour to thriving citizens contributing to their communities. This is done with enabling support rather than any focus on navigable services. It’s achieved by people being helped to change how they see themselves and the world.

If this is something services can’t do, they can instead work on creating the conditions for people to access their own capability to thrive. This will always be an experience unique to each individual based upon their own context. It requires any input from services to be bespoke-by-default and enabling rather than just intervening.

If the key is to thriving is one’s own capacity for internal, intrinsically powered change, then this does not obviate the need for public services, but it does create a different purpose:

“Help me access my own capacity to thrive”.

So as a focus for reform, rather than defaulting to bolting together a series of treatments and transactions that match peoples observed and/or expressed issues, might we look to work with people in partnership to help create the conditions for internal change for people each and every time?

The variation needed to do this is something that could never be pinned down into a process or a pathway. Only people whose role it is to build relationships could ever hope to absorb this variety.

We know from research into complexity and public services that attempts to mimic such complexity into complicated organisations and processes is ineffective as it fails to capture the nuances that matter to people and create the conditions needed for internal change. This ‘boundary’ between complex (people, relationships) and complicated (services, processes) is often problematic with people becoming coded as a series of problems that related to services, something we call pixelation. Any service would do well operate on the basis of relationships, which can absorb variety, rather than processes, which cannot.

By doing this, we are able to set out a more realistic and effective role for public services, i.e., to actively create the conditions most likely to enable people to access their internal, intrinsic capacity to thrive.

Because this is unique to each individual, any service would need the capability to be bespoke-by-default. This becomes possible when services are framed around empowered relationships between caseworkers and citizens. It is this kind of relationship that has formed the basis for the Liberated Method. At its core is the understanding that people’s internal changes are critical, but they can be helped with that.

Liberated Method – Balancing Extrinsic and Intrinsic Resources

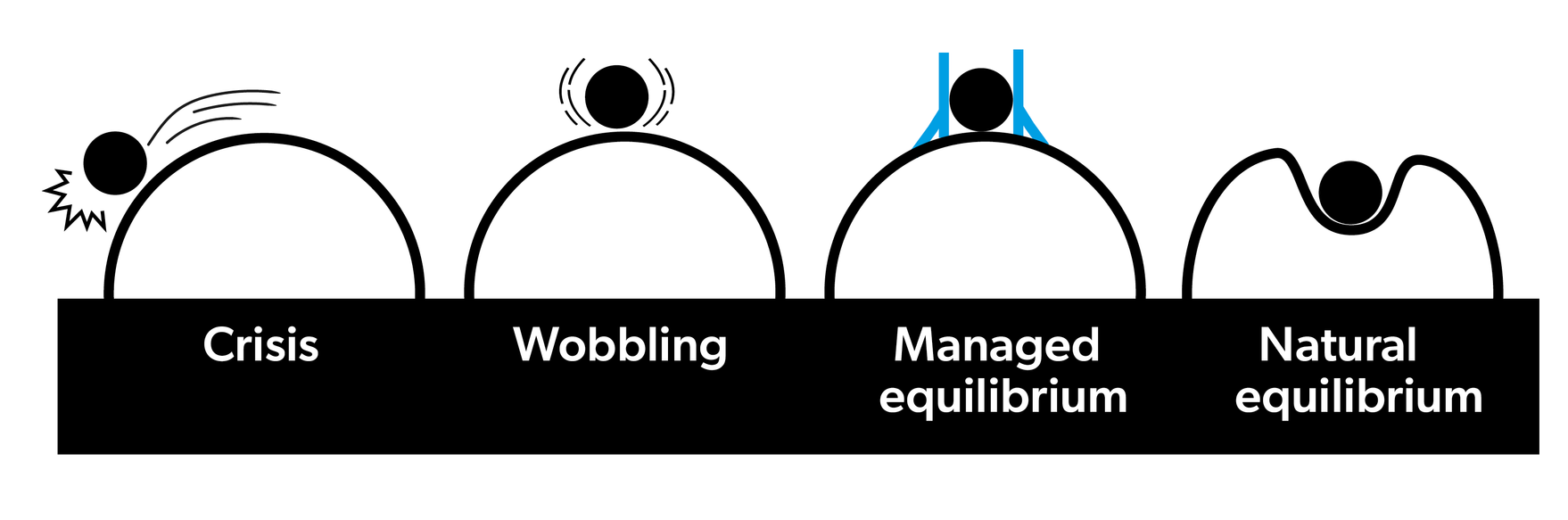

Accessing that intrinsic capacity to change requires some stability. It’s hard to focus on the future or on one’s own internal strength and power when the present is traumatising and there are pressures on all sides or fears for one’s safety. When people are in crisis and have several interlocking problems, their view of themselves and the world around them creates barriers and distractions that prevent them from accessing that internal capacity.

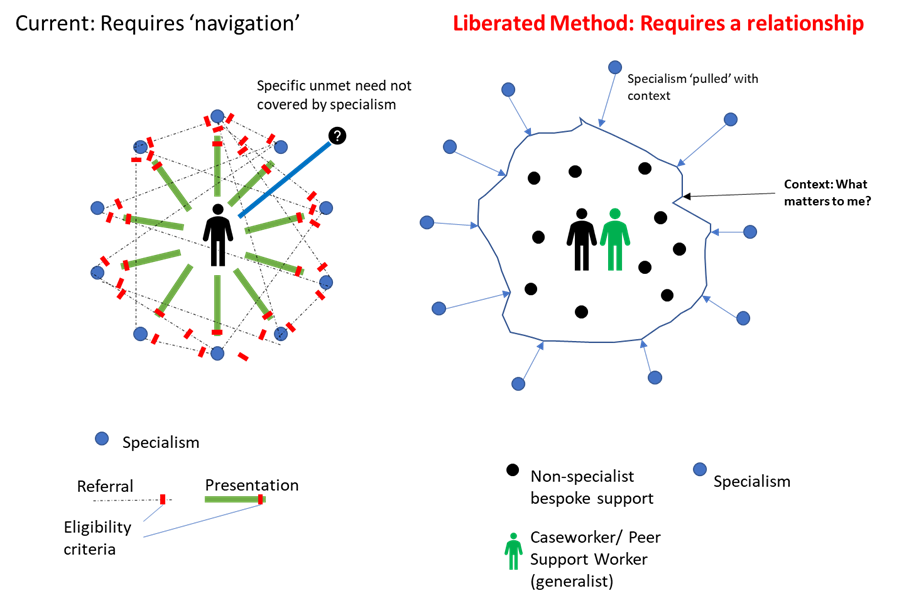

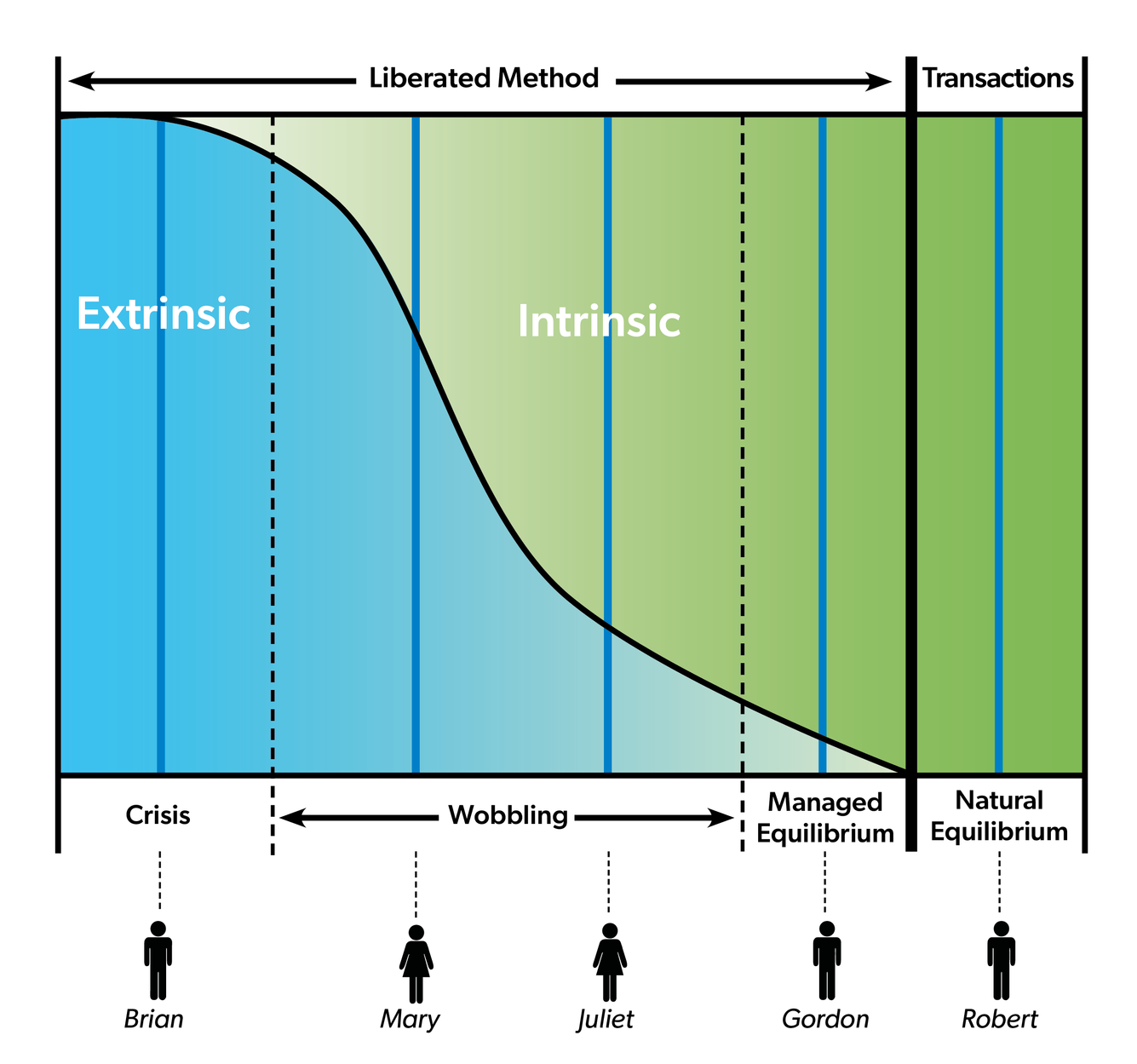

The Liberated Method is cognisant of this and therefore involves two broad types of activity:

- Extrinsically resourced – This is based upon a relationship with a caseworker who provides extrinsic resources beyond what people have access to. The purpose of this is to work on practical barriers and build emotional resilience and trust such that things stabilise. This stability provides a better chance of someone being able to access their own internal capacity to build towards a better life…

- Intrinsically resourced – This is someone’s own choices, capacity and agency deployed by themselves with as much or little support as is required. It’s self-determination, community development and something that services can’t and shouldn’t try to do.

By way of analogy, the extrinsic resources are like a vaccine, whereas the intrinsic ones are the immune system kicking in.

This helps us get real about services – they can be critical, but we will not see effective outcomes if we don’t understand that our role as service providers is to help enable what people have within them.

These types of activity are not sequential. They overlap. For most people who have some degree of support, the Liberated Method combines these from the start. The method can start at any point, with some people only needing a small amount of extrinsic input (although small amounts can still be critical, as will be seen in ‘Gordon’s’ case later) with others needing a much larger amount of extrinsic caseworker led support before their own capacity is able to kick in. The general idea though is that people ‘move’ towards the right of the diagram above from wherever they start.

Extrinsic support and resources

The extrinsic support and resources are usually in the form of a low caseload caseworker who typically does not have a specialism (if they do, they aren’t acting through the lens of their specialism). This element of the Liberated Method which creates the conditions for someone’s innate capability to thrive is possibly the Liberated Method’s most idiosyncratic feature. It is characterised by:

- A high support, high challenge relationship based upon building trust. Initially there is a focus on providing practical support, especially when the starting point is towards the left of the image above (i.e., more towards crisis). This involves being present, attentive, pragmatic, and effective in dealing with solvable issues quickly (e.g., sorting out benefits, providing food or clothes). As longer-term goals relating to behaviours and strengths are worked upon after trust has been established, high challenge is more likely to feature to help people stay on the course they have set themselves.

- A low caseload caseworker is allocated. They have time and the ability to make decisions around using team resources without having to refer back to management, meaning they can solve short term issues in situ and take the sting of out some situations e.g., having no food, accommodation or ability to travel.

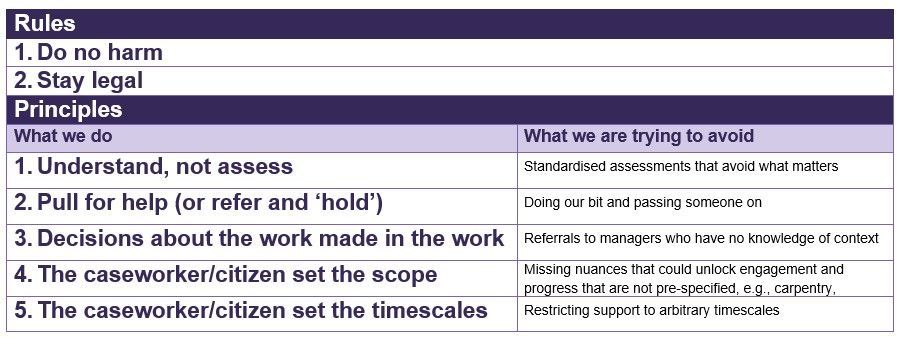

- The caseworkers operate within the liberated method’s ‘2R5P’ framework: two rules and five principles that guide decision making and frame the wider team’s learning and iteration. The rules have no grey areas, hence them being rules. The principles guide and are open to interpretation across the caseworker team and leadership. Iterating those principles through learning from the work is necessarily part of the liberated method. It has learning built in and this requires new behaviours of leaders and workers.

The casework teams have a running budget, and all caseworkers have access to it. It means they can buy coffee, get a bus pass, and do those things that unlock everyday problems and create the conditions for people to discuss longer term ones. This sounds prosaic, but getting anything simple and pragmatic done in the current set up is slow and frustrating. Provided 2R5P is stuck to, this can be spent on anything. The key to this is P.L.A.N – all spending must be Proportionate, Legal, Auditable and Necessary. Every receipt is audited and the spend analysed to provide some rigour but mainly to see what is predictable and whether some form of scale solution might help the teams for items that are often needed. This analysis is ongoing.

Intrinsic support and resources

This is the blossoming part, driven by the citizen with support where required. It’s where people become progressively less connected to a caseworker and more connected to their emerging community and network. It’s life, on a more sustainable footing. It’s where services should learn to progressively get out of the way (or at least take steps back) and let the universe do its thing.

This is truly bespoke by default; it can’t not be. Culturally, this works against a learned paternalism that considers input from services to be the mainstay of recovery and life turnarounds. They have a critical role to play, and often an ongoing one, but the goal is for services to always be in context and that absolutely requires that people access their own capacity to change how they see themselves and the world and for them to set the path.

The ‘extrinsic loop’

We’re learning that the segue from extrinsic support being the dominant to the supporting element of the method for any given citizen can be difficult. For some it happens naturally and there is no obvious point where this occurs. For others, the process of creating new relationships with caseworkers to move away from crisis creates a temporary stability that requires specific effort to phase out when things are calmer. It’s a form of inertia which might well be called the ‘extrinsic loop’, which people are nervous about taking over the reins or are relatively comfortable in an unsustainable situation and aren’t drawn to accessing their intrinsic capacity to change things.

The challenge to the Liberated Method from those defending standardised solutions is that this creates a dependency. It does, but not necessarily an unhealthy one. When someone is in crisis and has no one, it’s likely that building trust and being supportive during the extrinsic phase creates a dependency. But it’s one that can be effective in moving out of crisis and be surmounted when moving towards thriving. It’s a specific practice we’re developing, and it will feature in a future article.

Case study summaries: adaptability to various contexts and acuity

The Liberated Method is not a pathway with a condition and eligibility driven starting point. Anyone who needs support beyond the transactional can benefit from it, not just those in crisis.

At Gateshead, and more recently across Northumbria, we’ve developed this method across a variety of starting points. There follows five summary case studies from various Liberated Method prototypes that have operated in the last five years. They reflect starting points of various degrees of acuity. All the names have been changed in the following case study summaries. Some of the contexts have been changed slightly so as not to make anyone identifiable.

Brian

Brian was in crisis. He had no connections, no network, no hope (these are from Brian’s own account which he has allowed me to use). He was alcohol dependant and frequently attending A&E (the most frequent A&E attendee at the local hospital, averaging a visit every 1.5 days). He was offending and has a history of arrests and imprisonment. From Brian’s account and a major data trawl, we know that he has consumed a minimum of £2million worth of public services in recent years, mostly the health and criminal justice systems (this data and the method by which it was analysed will likely feature in a future article). Brian has had over 3,000 interactions with services in 14 years and yet remained fundamentally misunderstood.

Initially, he needed intervention. His starting point on the diagram shows that he was completely being pulled along by his caseworkers (all blue, no green) because there was a significant risk that he would die. The caseworkers worked on his accommodation and his treatment but encouraged him to think beyond his predicament and as such his interests and strengths emerged, this bringing in some of the ‘green’ on the model above. He ‘moved right’ on the model above fairly quickly. He’s now more towards the centre, with accommodation, connection, many weeks of sobriety and a longer-term focus. He’s consuming a fraction of the resources than in his past. The ability to act bespoke and to give him time and committed support was critical.

Services had failed him for 14 years.

Mary

Mary lived alone and had very little connection to anyone. She wasn’t drawing upon any services and wanted to live quietly. A family member was fraudulently drawing her benefit and giving a fraction of it to her, usually by sticking it through the letterbox. She was becoming ill. She lived in poverty and was unable to use the oven, which was broken, so cooked using a slow cooker. Often this meant food was undercooked. Neighbours raised concerns when they saw she was being sick in the back garden, but the response was that she had to self-refer.

Eventually, a gas engineer doing a mandatory gas check was concerned at the living conditions and contacted our liberated method prototype. We visited and found she was unwell, weak, with only the TV as a light source. The house was in a desperate state. She had sufficient agency to say what she wanted (to have a working oven because she liked to bake) and not much else. We pulled for help from the GP, and the police investigated the benefits situation and that was resolved by the team, who ensure she received her entitlement directly. We helped her get the house clean and furnished and the kitchen became usable.

She rallied when she realised what had been going on with her family member and she became determined to pull things around. We stepped back but not away and over time she got out more, connected with neighbours and, most satisfyingly of all, she baked. She was not eligible for any support she could readily access, and the GP was sure she was heading for death. But she didn’t need much, just enough to arrest a slide and for her to access her inner determination to live the life she wanted to live.

She would have never ‘self-referred’ and didn’t really know what that meant.

Juliet

Juliet was in debt. She previously worked a daytime and an evening job and that was enough to support her and her son. Her evening job was dependent upon her mother being able to care for her son whilst she worked. Their neighbour was abusive and threatening towards them and as such, Juliet’s mother couldn’t bear to come over in the evenings. Juliet had to give up her evening job and that’s when the debts grew. She became stressed and both her behaviour and that of her son deteriorated. She ignored the letters and withdrew from friends and family. Her son was on the edge of care given the concerns about her and him. The solution was to move, and as a council tenant, she could request a transfer. But the policy stated that she wasn’t eligible because she owned rent.

Juliet consented to be part of an early prototype of the liberated method. We were able to use the fact that we only have two rules (do no harm, stay legal) to ignore and bypass the housing policy (not law) and helped her to move. We supported her through getting some school uniform for her son (this was creating anxiety; we knew because we understood rather than assessed) and ensured she received in the in-work benefits she was entitled to. She’d been under paid for years and got a back payment. We were able to help her structure the debts and create some financial stability and sort the house move.

She did the rest: re-engaged with her sister, got her old job back, trained for a promotion and helped her son settle into his new school. She made the running, but we cleared the way. She was a ‘wobbler’ but was heading for crisis. We were able to put some props in to help her stabilise things whilst she hollowed out a more secure context for her and her son.

She was heading ‘left’; we helped her to ‘move right’ on the model below.

Thus, the Liberated Method is a prevention method (as well as an intervention as it was initially for Brian).

Gordon

Gordon was doing well, running his own business, and hardly ever accessing any services. He worked seasonally and his income was sporadic. This meant that his tax and benefits affairs were complicated. He was massively overpaying and underclaiming and getting into debt which was avoidable. His unusual income pattern meant that none of the standardised responses from HMRC or DWP would ever help him.

He needed a bespoke approach. The Liberated Method helped him simply by providing some help with his anxiety alongside a bespoke series of consultations from our DWP secondee. She got his affairs in order through a very personalised series of interactions with the wider system using her expertise. The extrinsic support was little more than that, but without it his anxiety and indebtedness were leading him to more destructive behaviours. This is what mattered to him and what he was afraid of.

He didn’t need us for much else and did the rest himself, so his starting point on the model above was very much ‘to the right’. Like Juliet, he was heading for crisis but was able to be helped to go the other way.

Robert

Sometimes the Liberated Method is not required, and a series of transactions is enough. Robert wanted help with a housing support issue. He also wanted help accessing financial support with care for his mother. His family and community were active in his life. Using his debt as a signal, we were ready to deploy a caseworker to help him over time, but he didn’t need it. He managed the situation himself and he wasn’t worried about the debt as he was about to restart work.

So sometimes a signal, in this case debt to the council, that suggests a need for extrinsic caseworker input just needs readily available transactions. Where people are well supported, this is more likely the case. Part of the Liberated Method is knowing when it’s not needed because people are already able to access their intrinsic capacity to solve and/or absorb problems.

So why isn’t this normal already?

Around 70% of those supported through the Liberated Method across four different prototypes in Gateshead and Northumbria have demonstrably positive upturns in their lives after periods of decreasing stability and even crisis. We know that the previous arrangements weren’t working for anyone we encountered.

It would be tempting to say that this is purely a system issue and thus systems need redesigning. There are indeed examples where the existing system does make it difficult to do the right thing, but we’ve learned that it is not as simple as that.

When we study the work that the liberated method allows the teams to do, particularly that stemming from understanding rather than assessing people, roughly two-thirds of it is agnostic of the existing system, that is to say there’s nothing to stop them doing this work now. The issue is that current pre-occupations (eligibility, compliance, budgets) don’t allow us to see the relevance of it.

This means we can do things ‘on Monday’. If everything is hinging on system change, it’s easy for people to ‘other’ the change required to a system change programme and swerve making changes to what they do day to day any time soon. Systems change advocates will tell you that there’s no change until the system changes. We’ve learned that this is not the case. We can do much of this quickly. I’ll explore this is a future, more focused article.

This isn’t to say that system change isn’t needed. There are system conditions that make doing person centred work far harder than it needs to be, even when applying the Liberated Method. Two-thirds of the value work is agnostic of the system, but one third is not and as such, there is systems change work to do. Plus, left unfettered, the system and its current configuration of services allows someone like Brian to consume £2million of resources to no positive and quite a lot of negative effect.

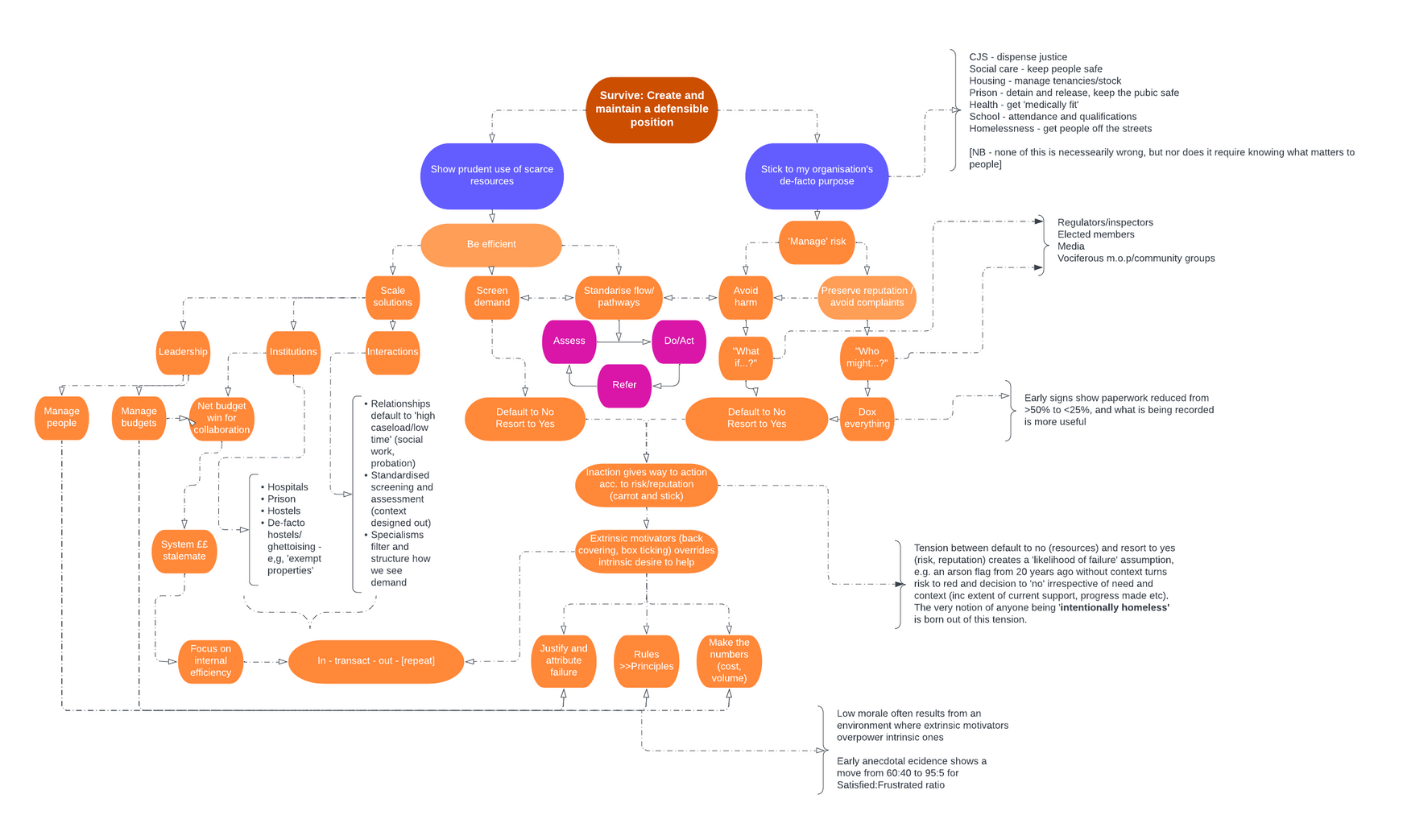

With the consent of those we have supported, we have investigated the history of consumption and interaction with services. Patterns are observable around the logics and behaviours at play, such that there are some common drivers across what are ostensibly different services.

Standardisation as a means to efficiency is reinforced by how services are designed and commissioned, and as such, we end up with one-size-fits-few processes that often miss what matters to people and things fail, thus creating failure demand. Commissioning that allows for iteration and learning, but also allows for practice to vary according to what matters to individuals would make the Liberated Method easier to apply.

Regulation and inspection has a role to play but is often predicated on the idea that quality can be inspected in. What it actually does is create a fear of straying outside a ‘safe’ bandwidth of options or methods and cannot absorb the variety that is people and what matters to them. Juliet being allowed to move, even though she had rent arrears, would have fallen foul of the fear of the consistency required by a regulator (or at least that was the perception) and thus she would have ended up in crisis and her child very possibly in care.

A resource stalemate also exists which makes it very difficult for any agency to focus on prevention issues or anything upstream of the eligibility criteria that defines their minimum service offer. For example, adult social care investing heavily in prevention would reduce demand into the health and possibly the criminal justice system, but it’s very unlikely that any savings made would find themselves manifesting as investments in adult social care. The budgets are buttoned down tight, and therefore it's in no service or organisation’s interest to ‘blink first’ and go hard at prevention. Instead, they focus upon internal efficiency which creates more failure demand as it goes deeper into standardisation and screening out.

When looking at key decisions in people’s service interaction history that have led to no help, ineffective (or even damaging) ‘help’ or partial/temporary solutions, there are a series of drivers evident that connect. This is a work in progress as Changing Futures Northumbria is still live, but the image below shows how these drivers connect and how they all have their roots in a single, super-ordinate logic, which is to create and maintain a defensible position. If we are to make the Liberated Method normal, we can proliferate those activities that are agnostic of the system right away and make significant progress. But addressing this issue is key and will require something different to do it, something that I will explore in another of this series of articles.

But aren’t people doing this now already?

Relational, strength based work and community development are well established and as such, our casework findings aren’t new. It’s important to understand that the Liberated Method doesn’t just operate at a casework level. To make this normal, leadership and governance has to be different (more focussed upon learning and enabling), method has to be different (using 2P5R and generally combining rules and principles rather than just using rules), scope has to be different, with relationships forming the scope rather than focussing upon navigating existing combinations of services (see image above), money has to flow differently to break the stalemate and ever allow prevention to truly happen, partnerships have to allow for caseworkers and specialists to believe each other’s information and be ‘pulled’ rather than referrals which require endless reassessment and masses of time and resources….

There are examples of method, leadership, scope, learning and partnerships all working this way, but nowhere are these things happening in one place. If liberated casework happens amongst orthodox new public management thinking, then internal consistency is lost, and the impact is going to be limited in scope and in time.

We’re learning that the Liberated Method shows itself in several realms, and in order for these changes to be possible at scale to take out huge amounts of waste and misery, these all need to happen at once. You have to turn all the levers to unlock this. We’ll explore this in more depth in a future article too.

What does this mean for public service reform and community development?

All these prototypes run the risk of only being valid in a bubble, created for experimentation. However, the analysis has extended into the substantive system and not restricted itself to what we’ve done. The use of narratives from our citizens and the digging of data (via 14 data sharing agreements no less!) means that we can draw conclusions and design an alternative outside of the scope of any bubble that we built.

What’s clear is that, even though much of what needs to be done to support people more holistically can be done now and is agnostic of the systems in public services, the rate at which current arrangements drive failure demand and waste makes it difficult to focus. There’s always a demand crisis to manage.

The stalemate thwarting public services’ ability to work proactively is particularly limiting and not easily solved. In North East England, devolution offers a potential opportunity to tackle this and thus our learning is well timed.

The creation of a new mayoral authority and resources that go with it offer a chance to build upon this work. The stalemate could be tackled if, instead of one organisation having to ‘blink first’, this work evolves to create some capacity and capability to support all organisations to do this in a way that turns all the levers and endures.

The Liberated Method has the potential to reduce demand, reduce waste and to be far more effective for people that need support in living their lives. We’ve seen it and are determined to proliferate whilst learning more.

We’ll keep honing the method, but what is encouraging is that organisations are seeing the results and pulling for our help now. To that end, we’re in the process of designing more touchpoints that will pave the way to hopefully establishing an Institute for Prevention and Reform in the North East that can turn the levers and create sustainable reform. This must not simply roll out caseworker practice, but help to develop leadership, develop evaluative practices that help everyone learn and have confidence in making changes and to proliferate the learning throughout organisations and stakeholders.

Future articles

This initial piece is intended to summarise the emerging Liberated Method, explore its evolution and the implications for the existing network of services and systems. There are some deep dives within the material presented that we’ll explore and put out some thoughts on in the coming weeks and months:

- A North East Institute for Prevention and Reform – removing the need to ‘blink first’

- The ‘extrinsic loop’ and thoughts on dependency

- Only all the levers can turn the lock – an exploration of how the liberated method would need to evolve across multiple realms

- Creating and maintaining defensible positions – why this ultimately drives everything

- What freeing up caseworkers and understanding people implies for team designs

There may well be others as we continue to learn.