An Institute for Prevention and Reform

Pulling Public Service Back Through the Looking Glass

© 2023 by Mark A Smith & Professor Hannah Hesselgreaves is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

Professor Hannah Hesselgreaves

Northumbria University

Mark A. Smith

Senior Responsible Officer, Changing Futures Northumbria & Director of Public Service Reform, Gateshead Council

23rd October 2023

Introduction

It’s not enough to be right…

It’s a freaky example of entropy that there are more reformers in public services than there are things to reform, and that both are increasing inexorably.

It’s not like people aren’t trying, but there’s something sobering in the lack of reform that we see, despite all this endeavour.

It isn’t because there aren’t enough people trying to solve problems. It’s because solving particular problems is the (relatively) easy part; far more difficult is making any solution normal.

Sustaining new practices is difficult because learning new stuff is easier than unlearning old stuff, and if public services are ever going to be liberated to reform around what matters to people, we need to collectively unlearn some long-held beliefs around such matters as how we lead, our take on ‘efficiency’ and what constitutes purposeful activity.

Unpicking what we believe about work and life is harder to swallow than coming up with that new, funky thing in a safe, experimental setting where the risk of the complexity of real life is safely managed. This is why many prototypes go no further, no matter how good their results. This article proposes a way of making learning and reform processes stick.

For anything to end up sustainably better, we need to do three things:

- Evaluate (what’s the problem to solve and how do we know?)

- Iterate (what solves this problem/ makes things better?)

- Proliferate (how do we make this better thing the thing we do from now on?)

Iteration gets most of the attention by those in the business of reform. We don’t often bother with evaluation (or we do it very selectively and/ or after the fact) because the locus for improvement is often bestowed upon us by others (regulators and executive leaders rather than citizens and communities) and as such, we aren’t really asking what’s afoot or studying demand. Proliferation, making it normal, is by far the hardest because it involves so many other people who weren’t involved in the iteration.

This makes life hard for many would-be reformers because, if we’re honest, people with the reforming skills aren’t often blessed with the influencing skills, nor are they often positioned to create the openings needed. So those working on reform in public service will iterate doggedly and shout about the results, hoping they get enough interest and curiosity. We’ve done this a lot. It’s not enough.

Public services, for all the effort and experimentation, have not significantly reformed in recent years, certainly not from the perspective of those that need them the most.

In this article, we’ll build upon the previous one by setting out how such a significant change in thinking and doing might realistically become normal and self-sustaining, and what we hope to do about that in Gateshead, Northumbria and beyond.

We’ve worked hard to learn how to get a bunch of things right that were very far from being so. But if we’ve learned anything in our pursuit of lasting change, it’s that it’s not enough to be right.

The Liberated Method and barriers to the mainstream

We’re certainly not the only ones working relationally, and many fellow travellers in this space can find themselves thwarted by the curse of having good results but no method or opportunity for proliferation. It’s worth noting that in the main, this isn’t because of what relational approaches are, but because of what the current state of play is. Put another way, it’s not the rightness of holistic working that’s the issue, it’s the intractable wrongness of an incumbent approach across public services that creates a de-facto purpose that amounts to creating and maintaining a defensible position.

This is a leadership problem, but it is also an ecosystem problem. The complexity of people’s lives and the vast complication of the ecosystem of public and voluntary sector organisations makes corralling the leadership group and staging an intervention pretty impossible.

So, to make the Liberated Method and other strength-based, relational, context sensitive methods the norm, we require something purpose-built within this ecosystem with the expressed purpose of cultivating reform. This is because there are a number of specific challenges that make it impossible to move to relational working with the configuration of services and partnerships as they are:

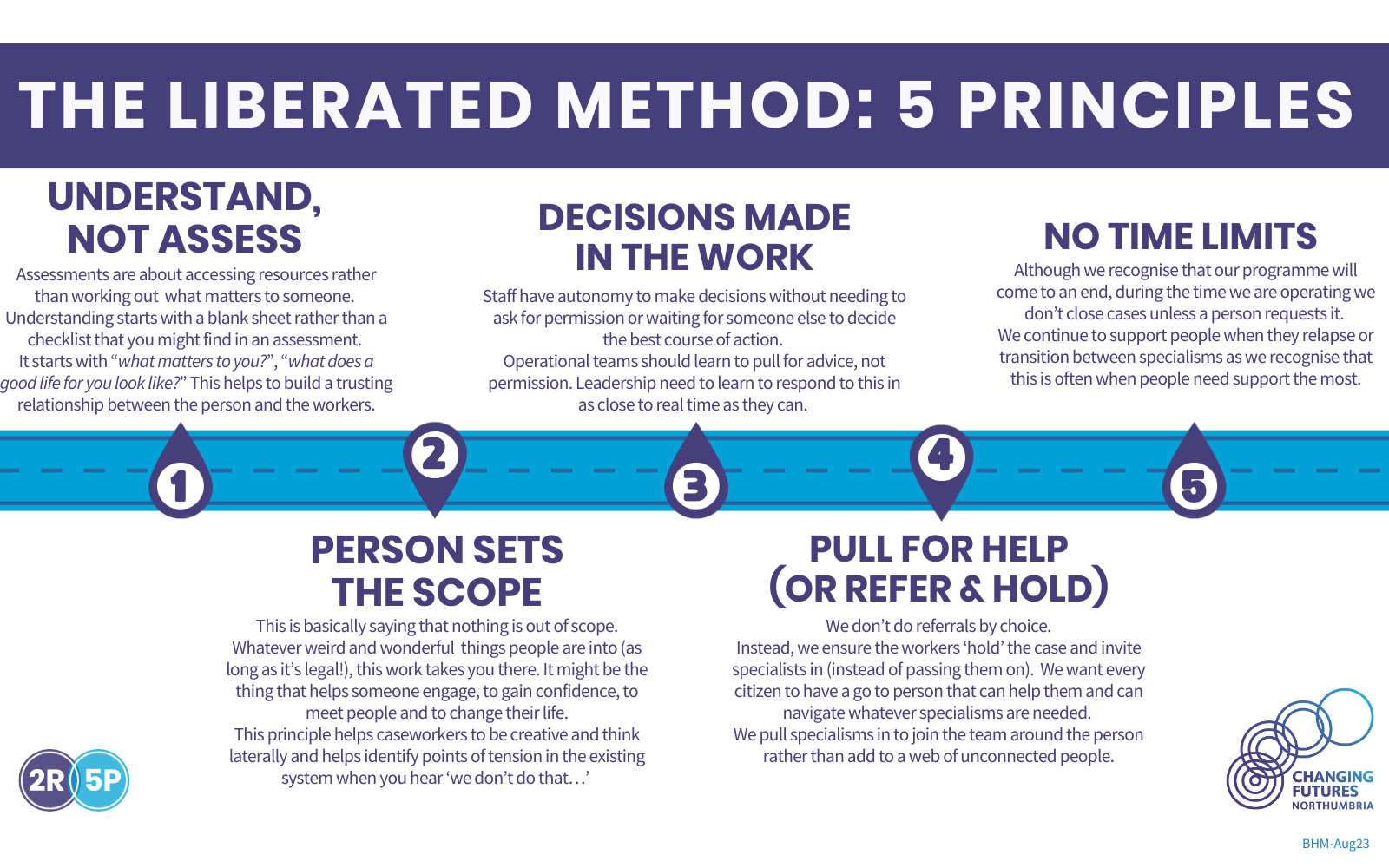

Budget capacity and flexibility

When moving towards relational approaches, the scope of the work increases. One of the principles of the Liberated Method (see appendix 1) is that the scope of the work is determined by the relationship between the citizen and the caseworker. This broadens it out hugely so that we’re covering more ground. The Liberated Method induces a ‘yes’ when we would previously have said ‘no’, which means that in the early stages, demand will actually rise before it falls sharply.

Because resources are so tight and tightly managed through eligibility criteria, defaulting to ‘yes’ rather than defaulting to ‘no’ as we do now is impossible without some dedicated resource to absorb this. We know from our work that this leads to a subsequent fall in demand and improved outcomes. The truth is that public services can’t afford to invest the capacity to improve through solving a broader set of problems with people. There’s no space to absorb a temporary increase in demand that leads to it falling.

There’s no capacity to sharpen the axe, so we just keep on chopping with an ever-eroding blade. If we’re going to reform, we need to invest in reform.

Stalemate – no one will blink first

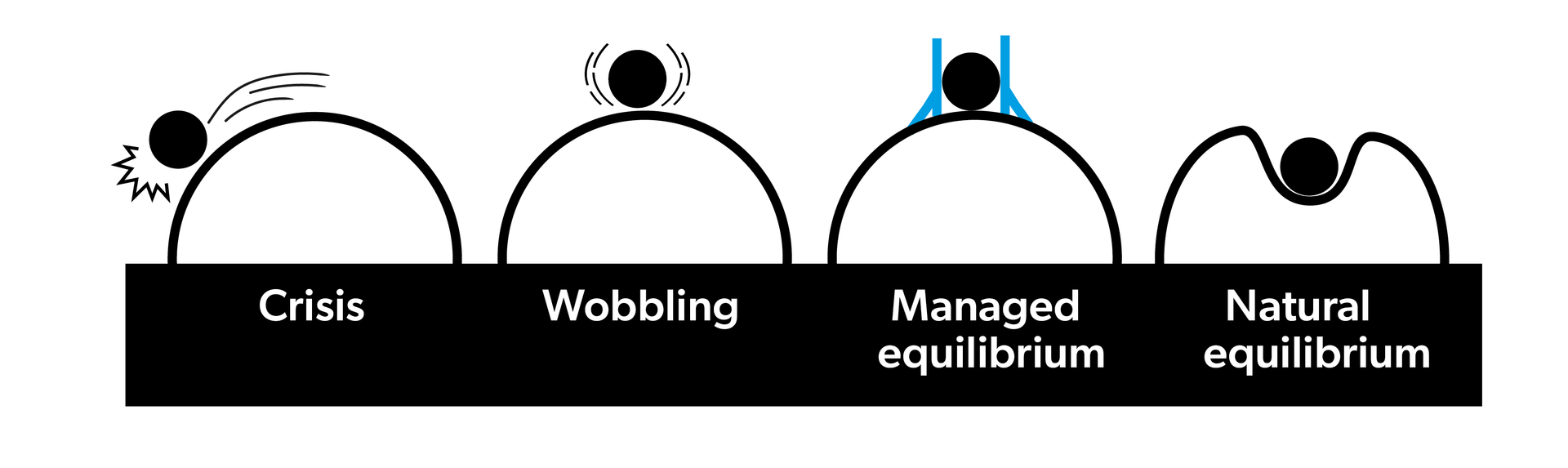

By working on what matters to people, but also being aware of the broader determinants of health and wellbeing, the Liberated Method often means that we’re working with a wide bandwidth of issues, ranging from those relating to crisis, those that are emerging and deeply preventative issues, potentially with the same person at the same time. Relational working spans the prevention continuum rather than focussing purely on whatever presenting issues fall within eligibility criteria.

This means investing in prevention and going past the brief for many public services, which means going beyond what they are funded for. Such bodies are still interested in this because they are savvy enough to know that prevention could reduce demand and pressure on their budgets. However, the way that issues and organisational remits do and do not intersect means that investing in prevention is not a simple matter, even though it ought to be.

If we consider adult social care as an example, investing in upstream activity that is beyond their eligibility criteria will stretch their already hard-pressed resources. But if they did this and demand fell, the main beneficiary would not be themselves, but services like the NHS. Given how budgets and, if we’re honest, cultures work, the NHS would not passport any savings they would see into a resourcing of social care input, it’s just not in their interest. This not just an NHS cultural issue, it’s a public service finance issue.

If things stay as they are without a specific and shared investment in reform, it will be left for someone to ‘blink first’ when it comes to funding prevention work to the benefit of all. But no one will, not least because they can’t. Financially, there is a stalemate that is a fundamental block to investing in reform.

Specific, shared resources and capacity are needed to break the stalemate so that for reform to happen, no one needs to blink.

Capability and a doomed focus on efficiency

Because the financial stalemate renders holistic and preventative work both pointless and damaging to short term budgets, organisations tend to focus their improvement efforts inwards instead to become more efficient versions of themselves. This not only doesn’t work, but it blunts our collective ability to focus on the changes that are needed. In particular, a focus on efficiency moves away from a focus on impact and as such, we don’t even know the extent to which our services work for people. Instead, we tend to know what we spend, how busy we have been and how compliant we are. This runs the risk of making poor service designs better at being poor.

Measures of industry are far more plentiful than those of efficacy and as such, it’s hard to know where to start when seeking to reform.

A focus on efficiency can also mean public services lose or fail to develop their capability to carry out reform work that extends beyond transactional, process or structure change. It’s marginal improvement at best, deckchairs on the Titanic at worst.

Only turning all the levers will turn the lock – extending beyond operations

The longer this goes on for, the harder it is to shake into being able to solve the problems that face public services and, more importantly, face those we’re here to serve. Even if we do create exemplars of better delivery through relational approaches, it is difficult to work out how to plumb into the wider system of budgets, structures, and governance which were designed for a different world view.

The Liberated Method in operations is not compatible with the rest of the ecosystem. So it’s not enough to work out how to make operations better, we need to adapt the rest of the supporting ecosystem too.

This is a far cry from focussing upon efficiency which would never be enough.

If we’re going to work holistically, default to yes, and broaden the scope of support, there needs to be some other key changes that must accompany those in operations, including:

- Leadership: A movement away from performative, transactional and inward focussed approaches to purpose-driven, citizen centred approaches. This includes using rules and principles in harness to ensure decisions can be made and learning generated where the work is done. It takes time and requires support to move to this way of leading as it requires a wider, collaborative focus on stewarding the system.

- System economics/ finances: The ability for resources to be designed or pooled around issues in a way that transcends organisations is required if prevention is ever going to be designed into public services.

- Commissioning: Determining what outputs are needed from commissioned work before it is delivered immediately constrains the methods and scope. This leads to narrow bandwidths of compliant activity which are never going to seriously make inroads into complex, bespoke problems. If we instead commission to learning, we are more likely to worry less about complying and more about working with people in a way that ensures their agency and context is material to whatever work is done.

- Governance: The work of public services reflects the structures of the organisations carrying it out more than the context of the person being supported. This is because decisions are made away from the work by those in senior positions (e.g., who gets what via eligibility criteria). The cascading upwards of information and downwards of decisions creates a governance approach that smothers any variety of nuance that is needed in the work. When combined with how we commission, it’s no surprise that public services are poor at understanding and absorbing variety, and nothing varies quite like people. Governance that fashions how we learn and iterate is much more likely to be able to support relational practices, and this requires specific effort, attention, and data.

Agency, and the fallacy of inspecting quality in

It would be far easier to create liberated governance, and deploy the Liberated Method generally, if public services were blessed with more agency over how they operate and iterate.

Public services are heavily regulated and inspected. This isn’t a problem in and of itself, but the nature of how it is done goes heavily into the realms of compliance checking rather than collaborative improvement and problem solving. Public service leadership is broadly nervous of inspections and often have pathological relationships with regulators, e.g., fear, resentment, and an instinct to put on one’s best face. This creates a de-facto purpose, i.e., pass the inspection, and moves away from a focus on learning, iterating, and debriefing (which many professionals are specifically trained to do). Imagine if regulators and inspectors were liberated to build relationships with services that enabled honesty, openness and a shared commitment to improvement…

As it is, regulators operate on the basis that quality and efficacy can be inspected into organisations which are the same everywhere. This means that any improvement efforts are dictated by the inspectorate rather than the citizen and as such, the motivation to be sensitive to the almost limitless variation of what matters to people is outgunned by the need to get a good rating. It’s human nature to defend one’s position, and so it’s no surprise that this is what takes over when there is a sense of being in any form of existential danger.

This is a significant barrier to being able to comfortably adopt the Liberated Method, even if the evidence shows that it gets better results.

System change: ‘Othering’ the reforms we need to make

There’s no doubt that the ecosystem of services and organisations needs to reform how it operates to better support people who have a lot going on in their lives. Changing how we lead, commission, govern and assure all require some form of change to the systems of work that operate in the public sector.

In our work across Gateshead and more latterly across wider Northumbria, we’ve applied the rules and principles of the Liberated Method without actively working on the system (instead, we’ve kept it at bay and deployed countermeasures). This enables us to use prototypes to learn how much better practice can simply emerge by increasing the bandwidth of method and permissible activity and how much of this really does need the system to change for it to become normal.

There are many classical systems thinking theorists who would say that no change can happen without system change, whereas we’ve found something quite different.

By allowing the Liberated Method space to breathe, we’ve been able to monitor the activities that have led to positive changes in people’s lives that were not previously happening, and in turn, we’ve been able to ascertain the extent to which these activities would need system change to make them normal or whether they were agnostic to the system and, as we say in Changing Futures Northumbria, could be “done on Monday”.

By holding the view that no change can happen without system change, leaders (in particular) that do not want to change anything are easily able to ‘other’ the changes needed to system change activity that they see as the preserve of others or that they cannot do alone. System change is an elephant that no one can begin to eat, and so waiting for it becomes a Godot-esque endeavour, and in the meantime, people can choose to stay as they are or focus on internally focussed change that’s easier (and often futile).

The data set is growing but as things stand, roughly two-thirds of the activity yielded by the Liberated Method to help people to deal with crises could happen without any system change at all. These activities were often simple but very deliberate and crafted, such as spending purposeful time with someone as they process the impact of a health appointment or providing a bus pass. This means we do not have to wait for systems change to change. We can start moving towards the Liberated Method ‘on Monday’. But demonstrating this needs the capacity, capability, and agency to experiment, learn and adapt. For this to happen, we need to invest in our ability to sustain it.

Devolution as a potential catalyst for reform

As things stand, public sector services are ‘through the looking glass’ regarding our cultural and systemic commitment to standardising and aggregating specialisms into what are seen as scalable solutions. If this were not the case, we might be able to learn our way out of this based upon our current configuration and mindset. As it is, we need something specific and disruptive that accounts for how deep we are into this; we cannot style our way out of this as things are now.

In 2025, a mayoral combined authority will be established in North East England, bringing with it a 30-year deal to invest in the region. Within that deal is a commitment to public service reform. This could provide the platform for building the capacity and capability needed to proliferate context-sensitive, relational practice, making it normal and widespread.

We believe a specifically created Institute for Prevention and Reform that could proliferate and iterate the Liberated Method would create fundamental reform to how we provide support for those that need it the most.

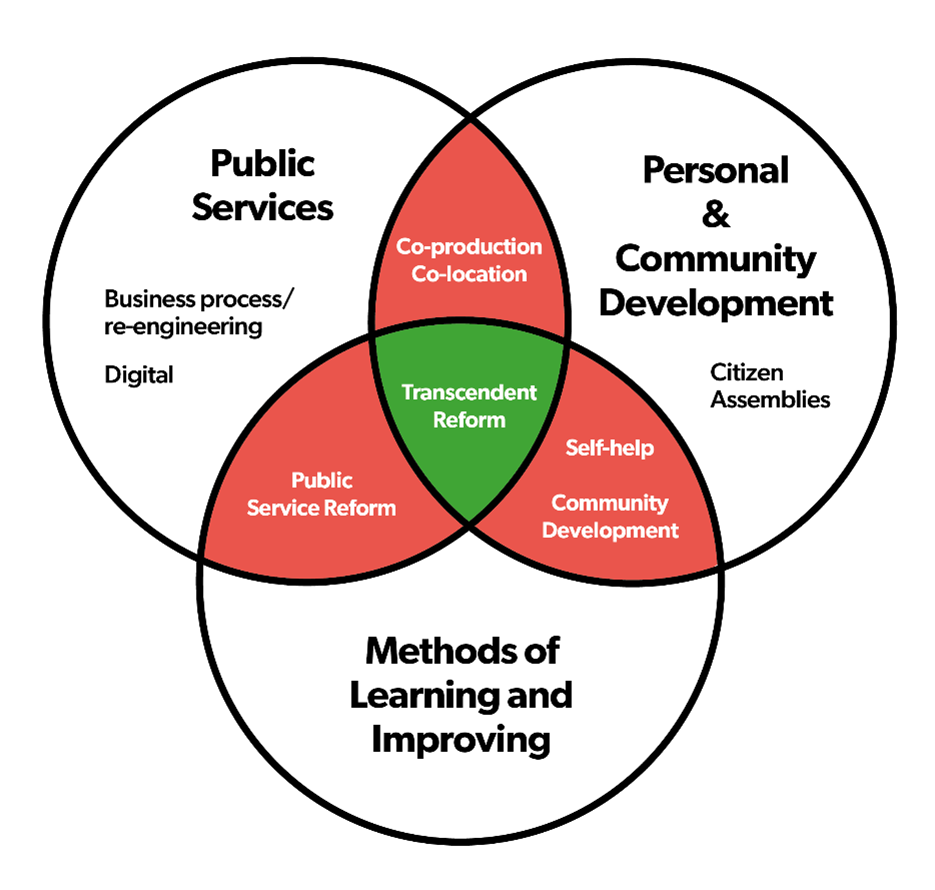

In our previous article, we opened by stating that we should stop trying to reform services because all we’d end up with is services. So, a reform programme that looks like a basket of services is unlikely to do much more than create leaner versions of things that don’t work. Instead, we offered that basing reform around relationships was far more likely to effective, with contexts providing the elements to any reform programme. Building a reform programme that deploys relational methods such as the Liberated Method to contexts rather than services (such as homelessness, leaving prison, leaving care) is more likely to result in transcendent reform that makes a profound difference to many lives and goes beyond the usual service led approach to public service reform.

If there is commitment to such reform, there must be an investment in it.

An Institute for Prevention and Reform

To turn all the levers at once (operations, leadership, governance, finances and commissioning), we need to design internally consistent logics into all these key elements of practice and its conditions. This is exactly a quality of how the existing system managed to proliferate and embed so successfully – and equally why it’s so hard to dismantle: all the levers are compatible with each other.

When we introduce new initiatives in operations, they need protection from the incompatibility of the ecosystem around them, placing restrictions on those initiatives to proliferate beyond their defined, funded, bubble. This makes prototyping and experimentation difficult to embed and as such they wither on the vine. One wonders how a cost-benefit analysis of projects without supported legacy would appear on the public balance sheet.

So, alternatives in operations need compatible levers elsewhere too if they are to sustain and unlock transcendent reform when the funding bubbles burst.

We suggest an Institute for Prevention and Reform (IPR), a ‘neutral’ entity, owned by everyone and no one, which will design compatibility across these levers, and liberate not just a method in operations, but leadership, data, and public finances. It would work on reform beyond the bounds of services, and along the prevention continuum.

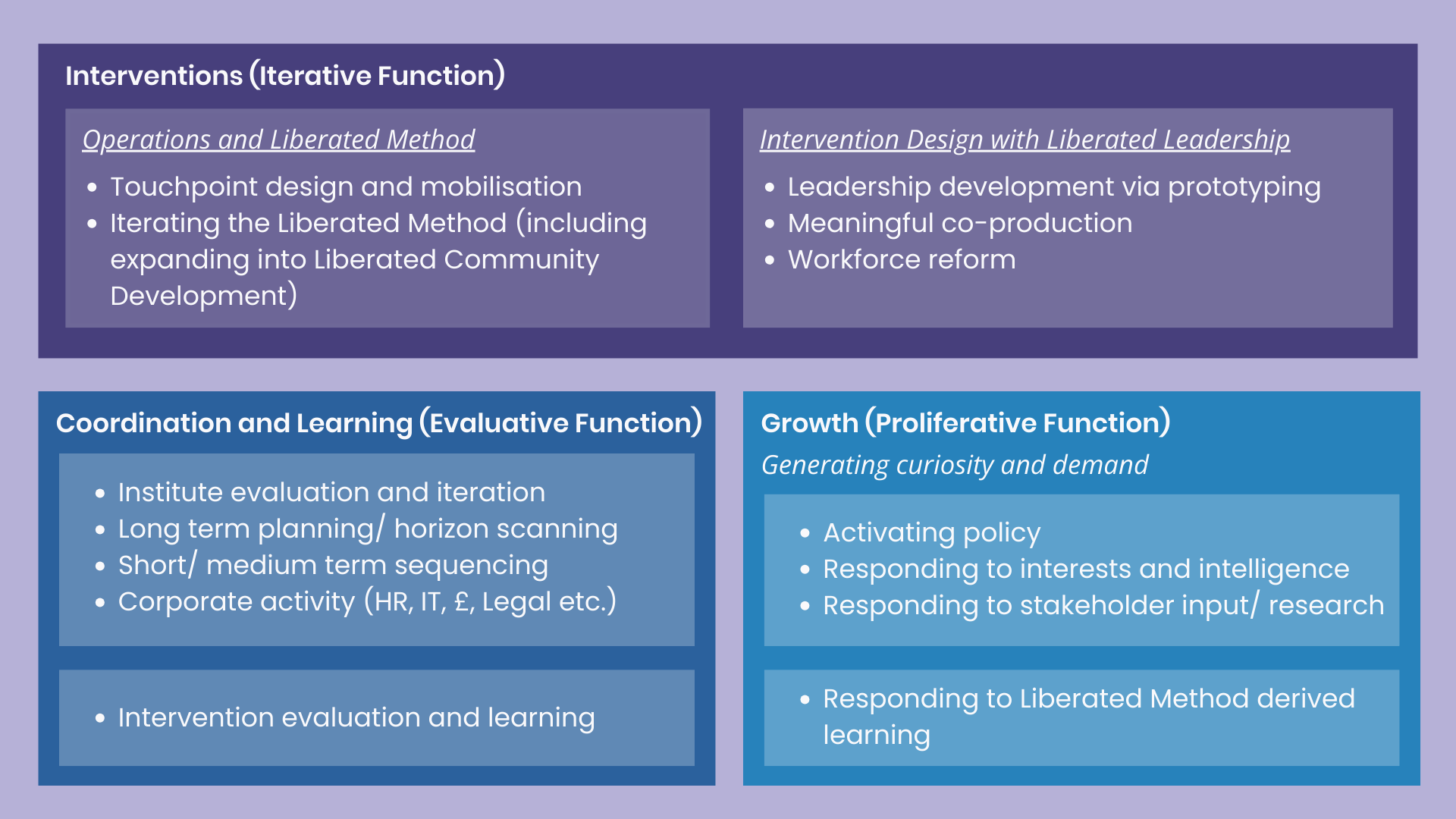

This IPR will be a method-based learning organisation that works to generate consistency in the conditions needed to mainstream learning from the Liberated Method. This means that we design it to:

- Iterate its practices in interventions (organisational learning),

- Evaluate its work and itself (a learning organisation), and

- Proliferate by generating and responding to curiosity, demand, and intel generated by the evaluative functions and external interests.

Deploying and iterating the Liberated Method across Gateshead and wider Northumbria has induced a significant amount of curiosity from a variety of leaders and specialists across the ecosystem of public and voluntary services, within and beyond our geographical area of operation. They have been keen to explore the consequences of adding context to specialism as a feature of the design of work exemplified by the Liberated Method.

This results in them wanting support to develop a variety of reform initiatives, such as bespoke by default interventions in their locality to help a problematic client list (such as hyper-regular attenders at A&E), touchpoints to experiment with complex, layered delivery agendas (such as locality working), or policy-makers and regional agenda-setters seeking tried and tested ways of bringing their policy priorities to life (such as homelessness and rough sleeping).

These represent different points of entry to the engagement of the IRP. Therefore, our proposed design comprises of three core functions: intervention work, coordination and learning work, and growth work.

We know the work must be about more than interventions and being right. But there is a lot about making this normal that we don’t yet know.

We are actively piloting the IPR to make bespoke by default and context sensitive methods normal in North East England to solve some perennial problems faced by the mental health trust. We’re aware that there is more curiosity and potential demand for interaction and support from such an institute as a movement towards relational, context-sensitive work grows.

Liberated Method interventions are the heartbeat of an IPR. They are the operational bits of designing, mobilising, and iterating relationships with people, through touchpoints. We’ve noticed that the more prototyping of the design, mobilisation, and iteration of relationships is done with significant leadership engagement, the more those leaders liberate their own capabilities to manoeuvre all the needed resources, giving the Liberated Method space to breathe.

This response from leaders also means they are close to the work, and close to its effects, meaning they liberate further capacity (from improvement teams, innovation teams, clinical teams). This is how internal consistency occurs generatively and creates an organisational footprint for further capacity for them to do more of it. But crucially, leaders understand what is required of them, and how to respond (typically unblocking work around permissions, spend, resources, attitudes) if they are part of the iteration work.

Then what? Iterate prototypes for ever more in the name of bespoke by default? That would seem logical in a world where people and their lives matter more than services. But it’s the bubble-version. Looping around practice based on the context-richness of the lives of those we seek to serve is great. But what do we do when the bubble bursts? The funding ends, the supportive Chief Exec leaves, the programme runs its course, a key piece of policy is pulled, the commissioning arrangements are no longer conducive.

We need to connect somehow to this environment if we are to ever make these things normal. We call this proliferation – working with the externalities in very specific ways, under very specific circumstances to grow the Liberated Method across all the levers.

There are two ways of proliferating that leverage externalities. One is by attraction from a service landscape to a ‘live’, natural, complexity-led landscape. The other is bringing Liberated Method to policy. Again, neither are ever pulls from us. They are inquiries. The proliferation function asks: “what are we learning from the wider world that needs attention?”

As well as the contexts of people’s lives, we need to account for the contextual realities of all those crucial stakeholders, generalists or specialists, that are trying to help people. This doesn’t mean we necessarily succumb to their service landscape - their budget preoccupation or their fear of the regulator - but we acknowledge it. The experiences of some - of preoccupation and fear - are symptomatic of an ecosystem of services that has lost its way but is nevertheless rooted in something positive about the notion of service or support. Public service is inherently benevolent, but budgets and regulation are snagged up in a risk-mindset (the one that defaults to ‘no’ and resorts to ‘yes’), which renders many who work in delivery conflicted.

When we use responsible and compelling data to show and explain how the Liberated Method reduces consumption and improves outcomes, it seems to have a pull on these people. Stories and narratives are powerful tools for communicating impacts which generate curiosity and demand for the Liberated Method. This is part of how attraction can happen. And why proliferation (interestingly, a stage in wound healing where new cell growth happens) is a deliberate endeavour for an IPR that’s discernible in the design.

The other way of leveraging externalities to proliferate is through enacting and implementing policy. This is really a tautology, since definitions of policy centre on ‘courses of principles of action’ or ‘conduct’, or ‘what to do if…’ (policy is a plan of action) but as so much policy-led work now seems to centre on priority-setting and setting out positions and agendas on key topics, an IPR can deploy the Liberated Method to turn these agendas and priorities into activity.

The IPR would provide methods that enable policy to be effective. Where there are deep and enduring social concerns (e.g., inequalities, obesity, poverty, loneliness), policy fault-lines have existed for several decades, so they are resonant seed beds for approaches that are incremental and adaptive, building on the existing beliefs about these problems, and layering on active interventions that transcend individual problems. This moves evidenced-based policy from its roots in rational choice theory towards policy based on compassion and complexity. If done well, the deliberate and skilful connection of method to priorities and agenda will attract energy towards innovation and reform, rather than persuade and cajole policymakers to go along with it, unmotivated, and without really investing.

This creates ‘Liberated Policy Making’ as an element of the wider Liberated Method, connecting policy, strategy and operations where New Public Management and a focus on efficiency has riven them apart.

Evaluative work is the purpose of the coordination and learning function in an IPR. Just like iteration, evaluation is designed in at the start – rather than becoming an organisation that learns stuff, we design a learning organisation that enhances capability to iterate but also to advance wider practices and approaches. We reference evaluative practice here rather than evaluation: this work isn’t discrete from operational (intervention) work, and it doesn’t end.

Evaluative practice in an IPR involves a dual focus. One is on evaluative practices of the interventions, to iterate with confidence, and ensure that decisions about iteration are based on data that is responsible (context-rich, never assumed to be static, and focused on what matters, not just what works). These are not nice-to-haves in complex evaluative work, they are fundamental. This work is asking ‘what do our interventions tell us we need to do or do differently?’. In Changing Futures Northumbria, this form of evaluative practice is conducted in team debriefs. It’s where critical analysis, sense-making and learning happens, and it informs practical changes in the work.

Digital learning and communication platforms, that are governable and secure, are being developed to support the recording, communication, and management of information generated through sense making and deliberation in various meetings, including team debriefs. The platform will uniquely support the continuing evolution and reconfiguration from within the work so that it's always doing something helpful: that learning and communication services the work, and not the other way around.

The other focus is on evaluative practices of the institute itself, to collect and synthesise the lessons from interventions, and use those for making meaning. It asks something like ‘what capabilities are we fostering that enable us to proliferate?’ It also provides cues on the timing, sequencing, and planning of the institute’s work. Crucially, this function enables us to examine what measures may be important for the accountability of capability growth, rather than for the accountability of the production of outcomes.

Between the evidence from interventions (Liberated Method, Liberated Leadership, Liberated Policy Making etc.) and the curiosity and demand generated by proliferation, the IPR as a vehicle expects to iterate to accommodate what is learned. It’s in the evaluative space that policymakers, funders, and researchers would find intelligence about how transcendent reform can happen.

Far from being another bureaucratic entity enacting a structural response, sent to coordinate programmes of work, an IPR would instead provide stewardship for the Liberated Method. This is about developing adaptive capability – supporting the ability of public service systems to adapt to or pre-empt changes in their operating contexts. And it’s also about developing the capability of public service providers to act as responsible stewards of publicly valued outcomes and ensure the Liberated Method continues to iterate in alignment with that purpose.

Where now?

The idea of the IPR has grown out of several years of developing relational approaches to public service in Gateshead and more recently across Northumbria. We’ve honed a method that works for citizens but have also learned (often painfully) how this rubs against the existing systems and mindsets resident in public services. Both are equally important in understanding how we could achieve the reform we want to see that can reduce demand, inequality, and cost.

The advent of regional government in North East England provides a potential platform for the IPR, but that is by no means a given. This will only happen if the existing leadership, political and executive, are comfortable with the idea of a purpose-built institute to build capacity and capability in transcendent reform.

The level of curiosity and potential demand across the UK and beyond seems to demonstrate a wider potential demand for such a capability, and thus the IPR existing as a commercial or quasi-commercial entity is plausible. Much remains to be seen as this exciting movement towards relational reform gathers pace.

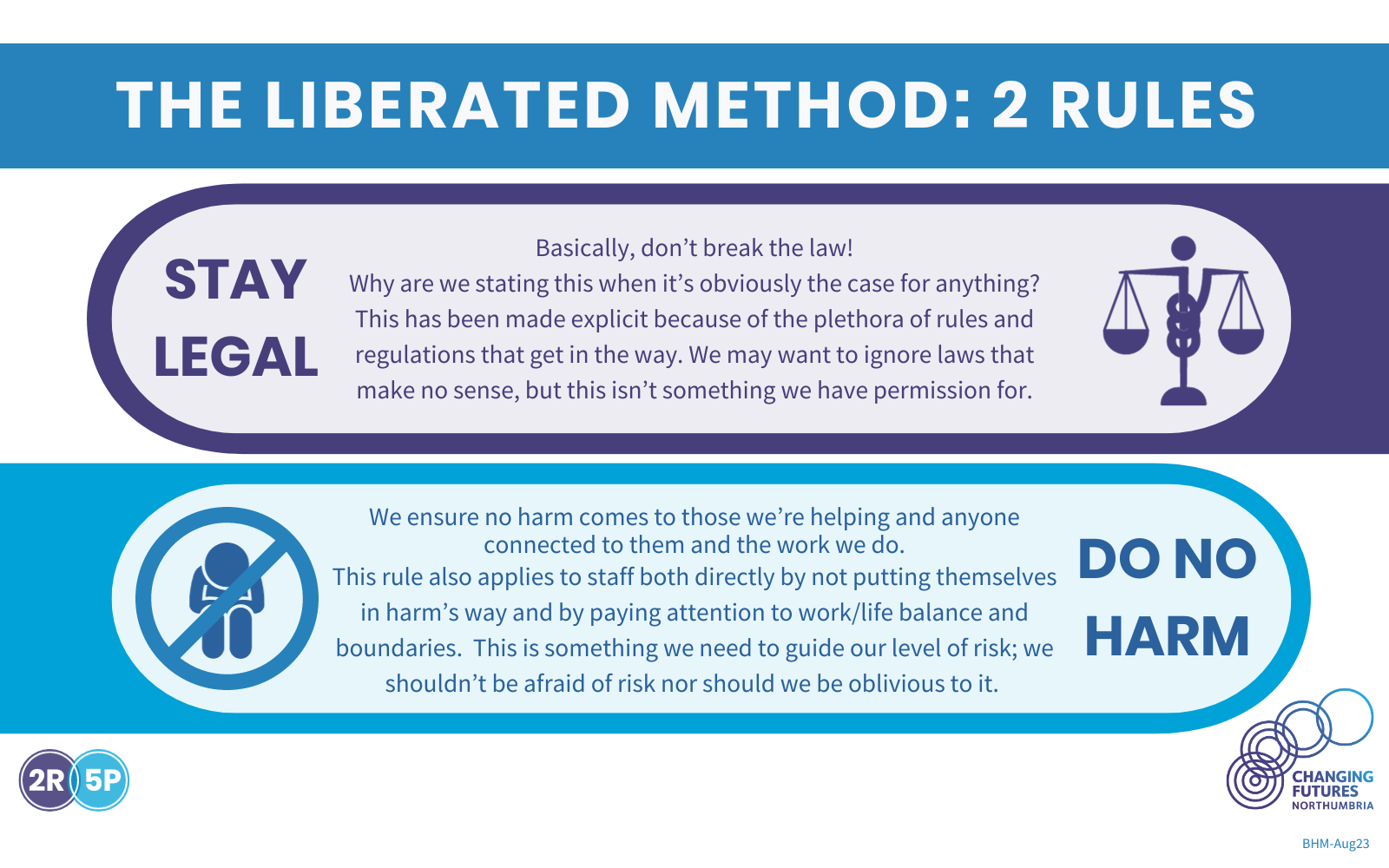

Appendix one – Rules and principles of the Liberated Method